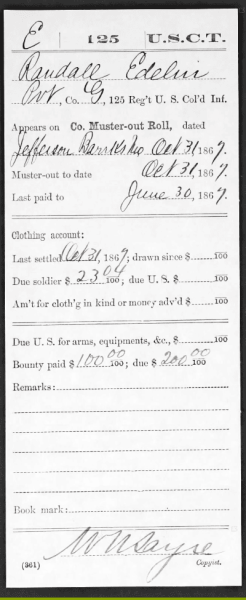

Biographical Profile of Pvt. Randall Edelen, 125th U.S. Colored Infantry

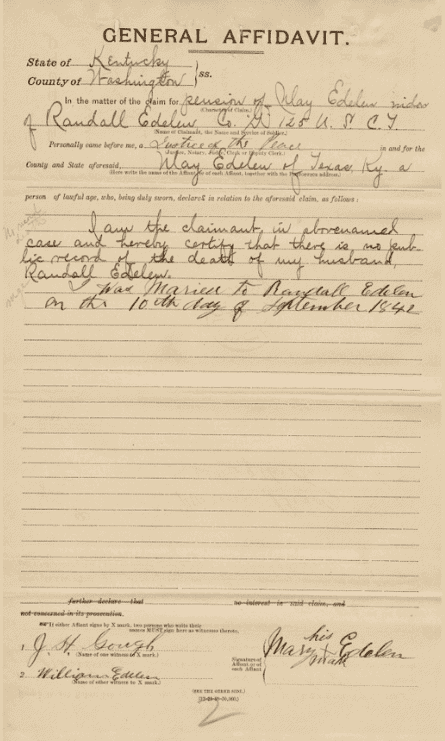

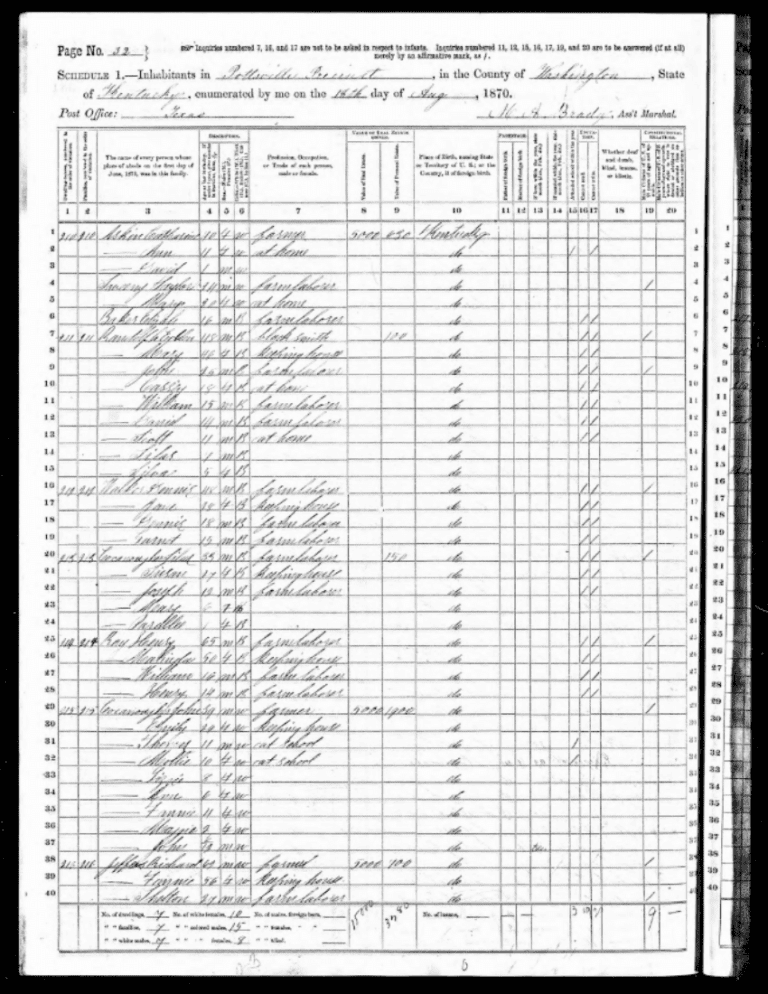

My 3rd Great-Grandfather on my mother’s side, Randall Edelen, was born in 1821 in Washington County, KY. He married Mary Edelen (Crouse) in 1842, and they had seven children (John, Susan, William, Sallie, Daniel, Scott, and Silas) together.

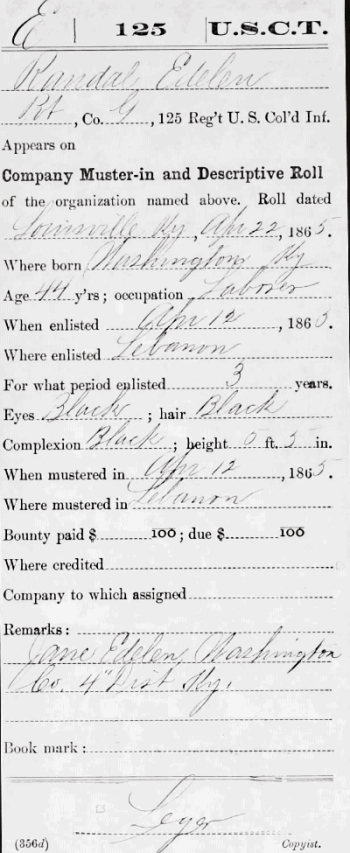

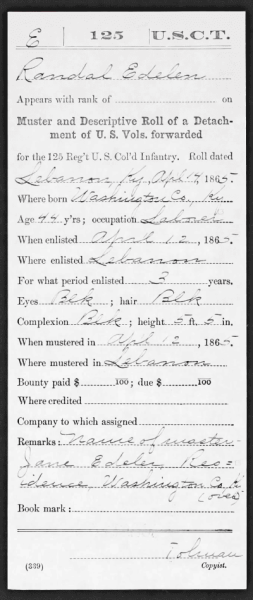

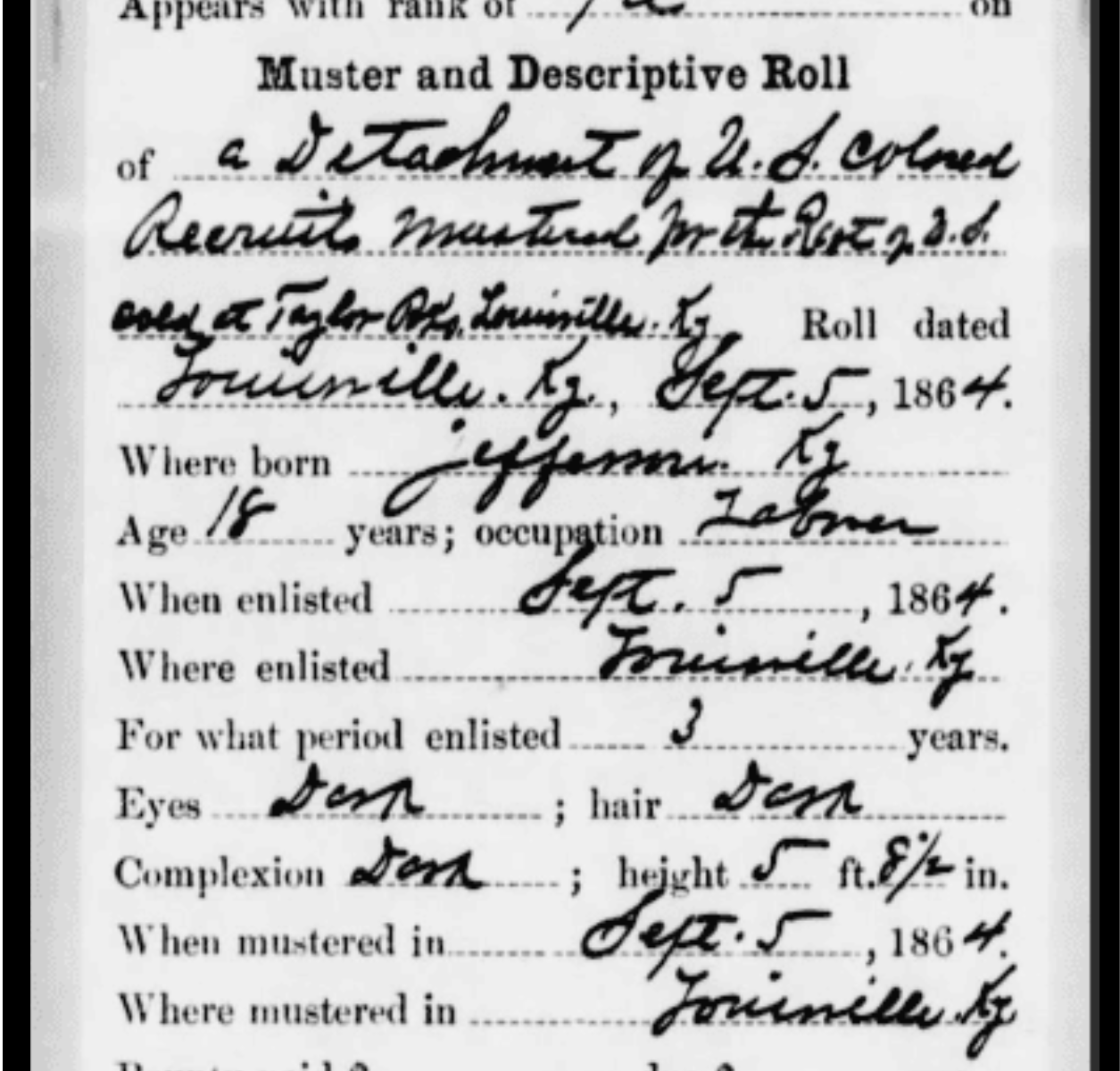

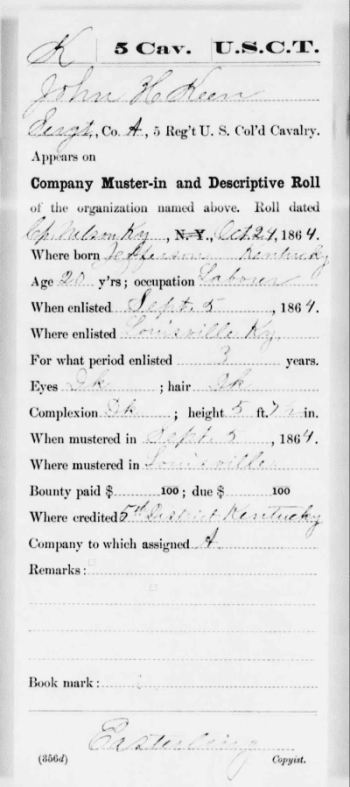

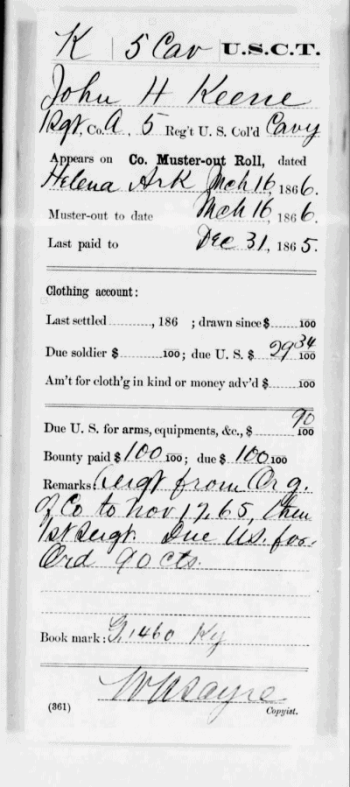

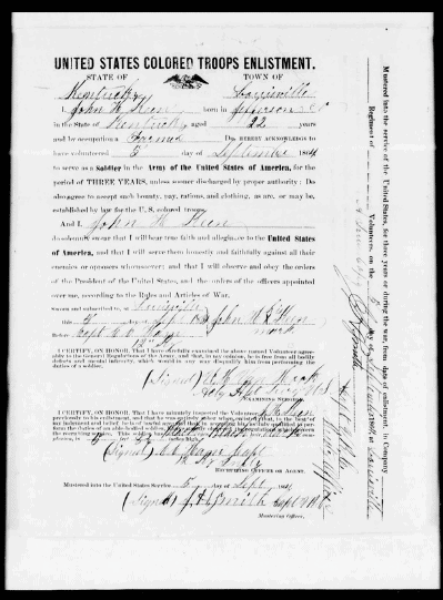

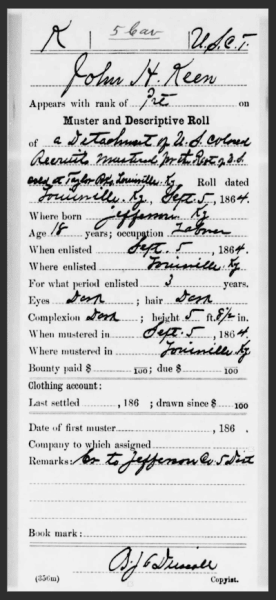

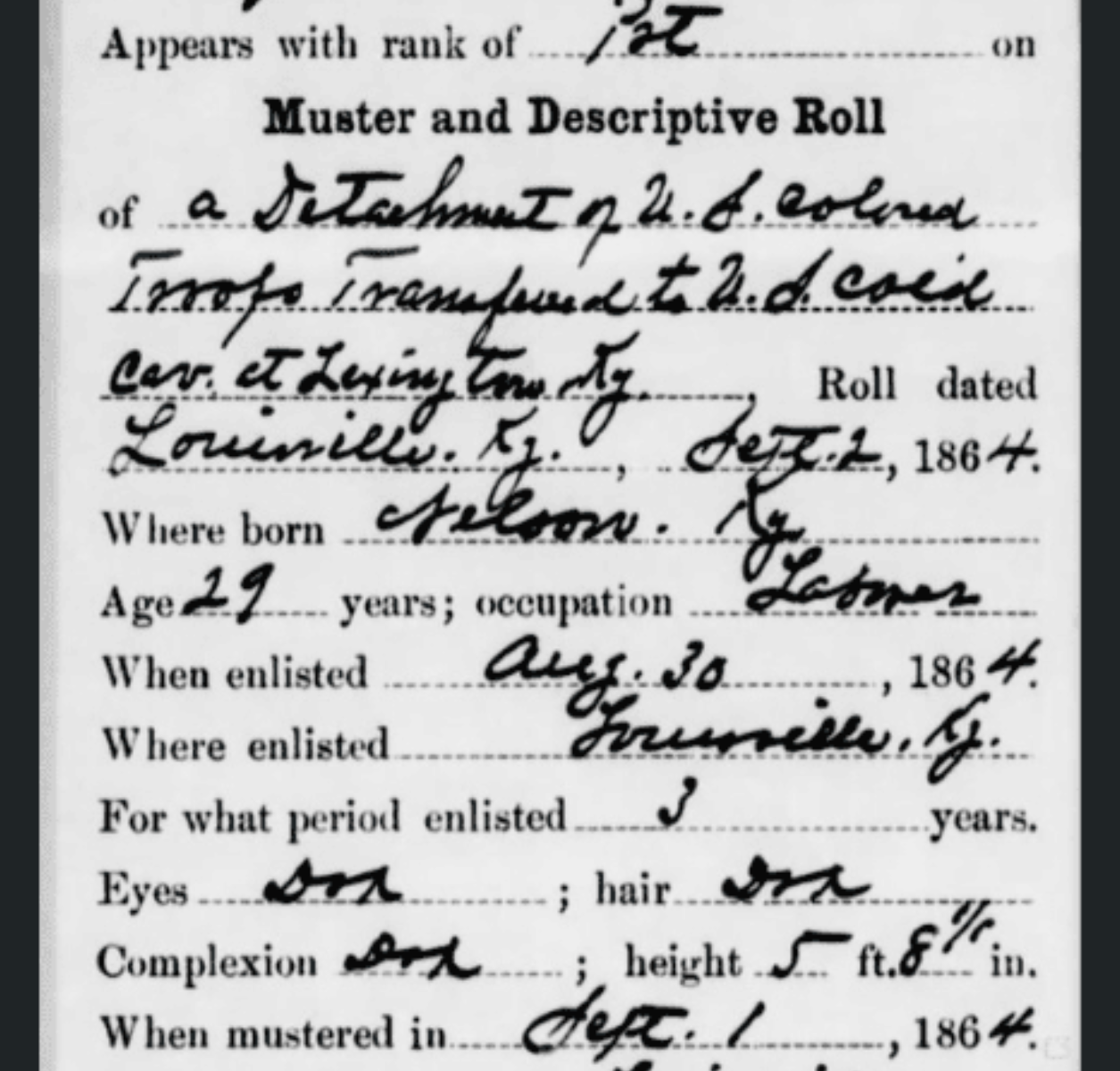

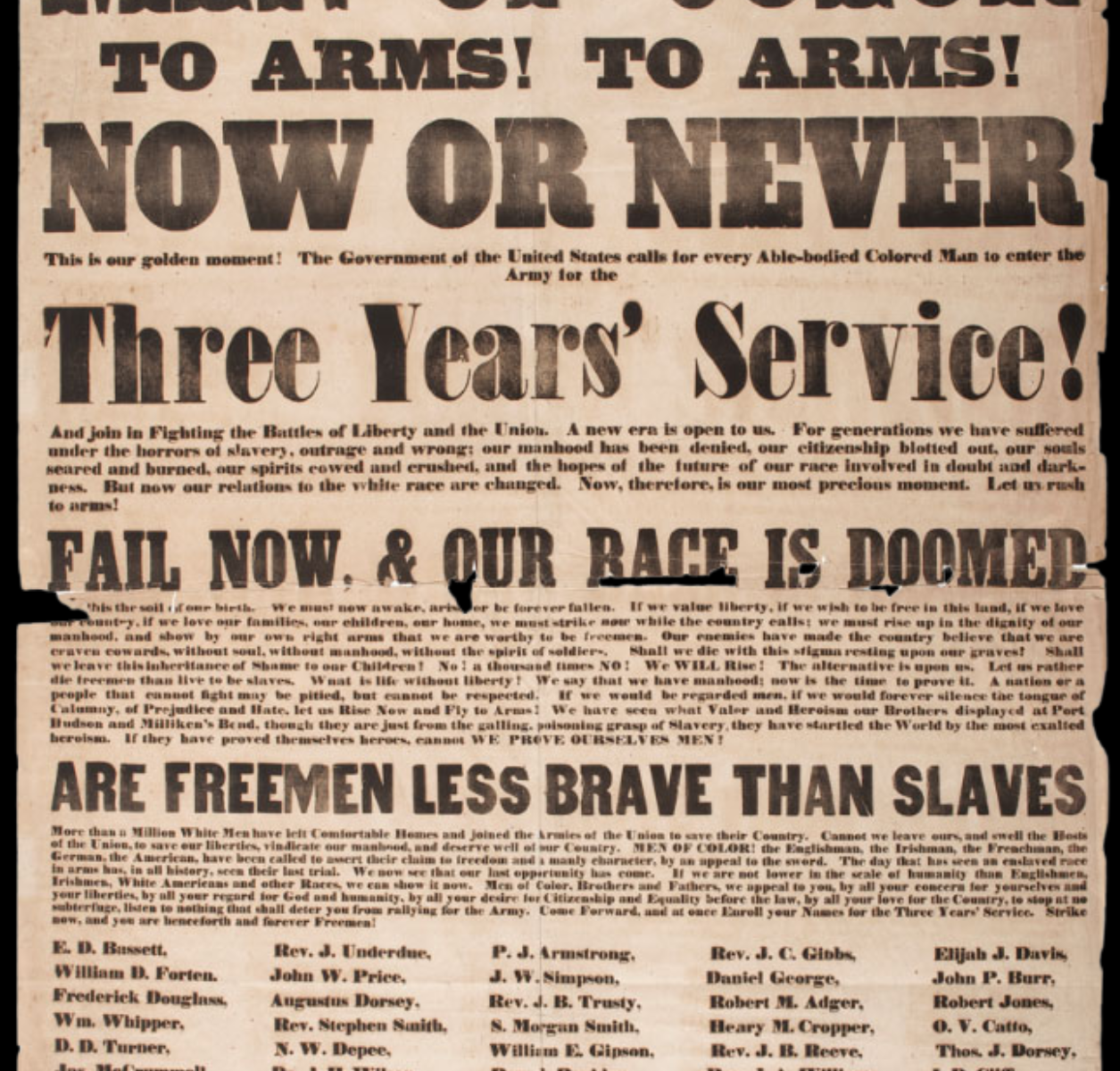

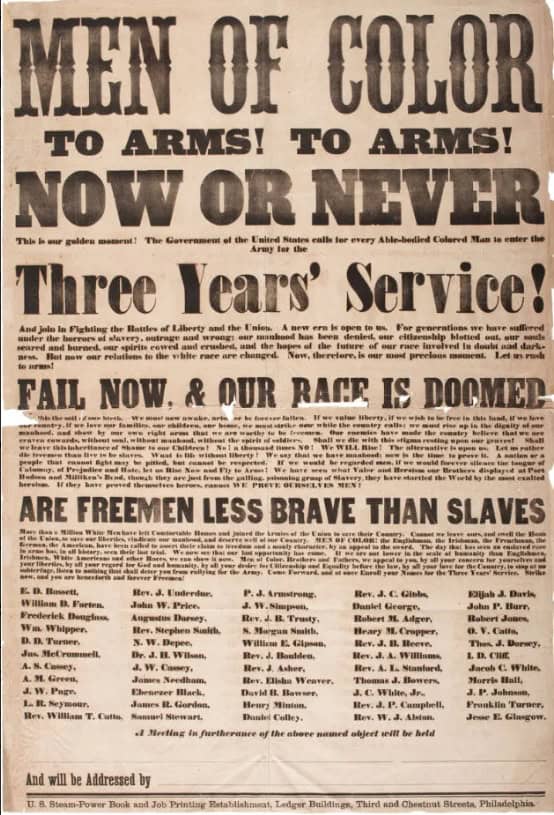

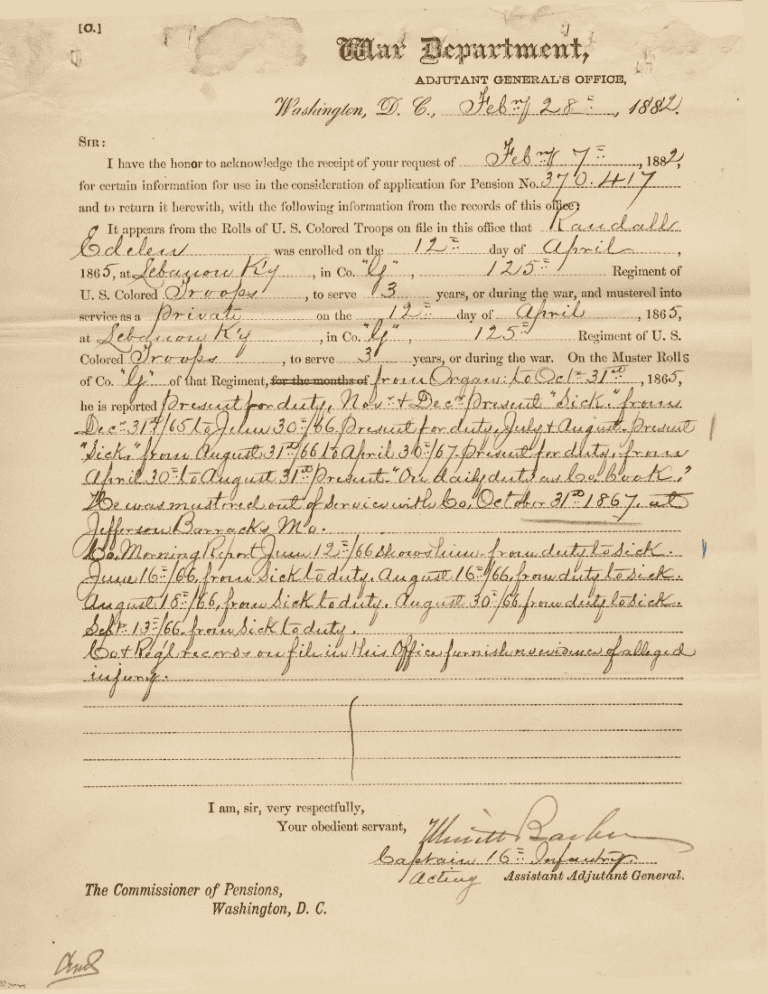

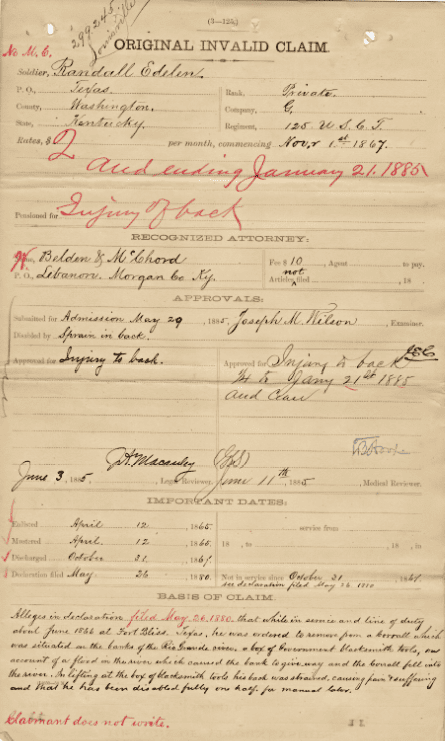

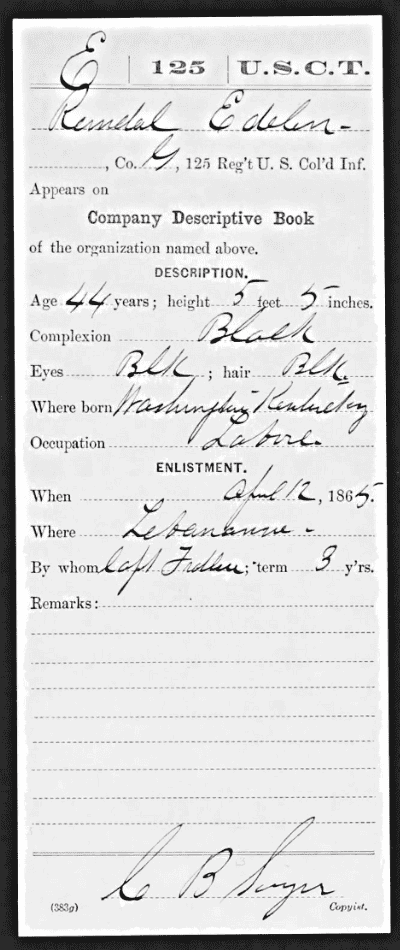

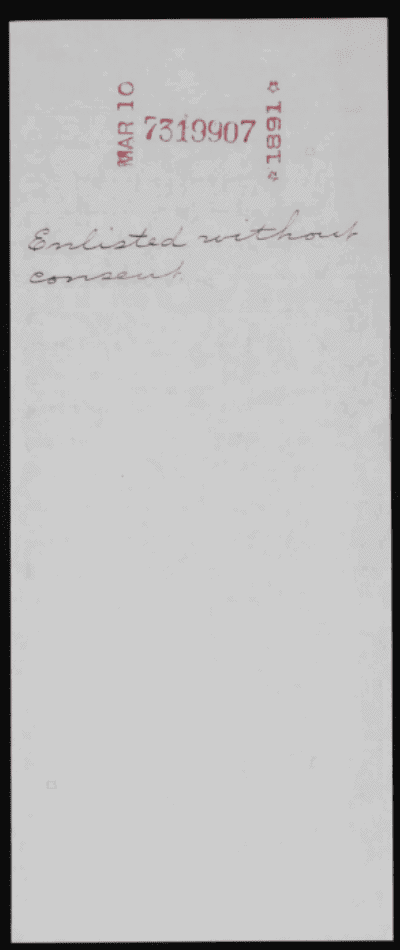

He enlisted in the Union Army at age 44 on April 12, 1865 “without consent” of his owner, Jane Edelen, a month after an act of congress guaranteed the emancipation of the families of all slaves who enlisted. He also had the additional incentive of earning a $100 bounty and $300 total at the completion of three-years of service for volunteering.

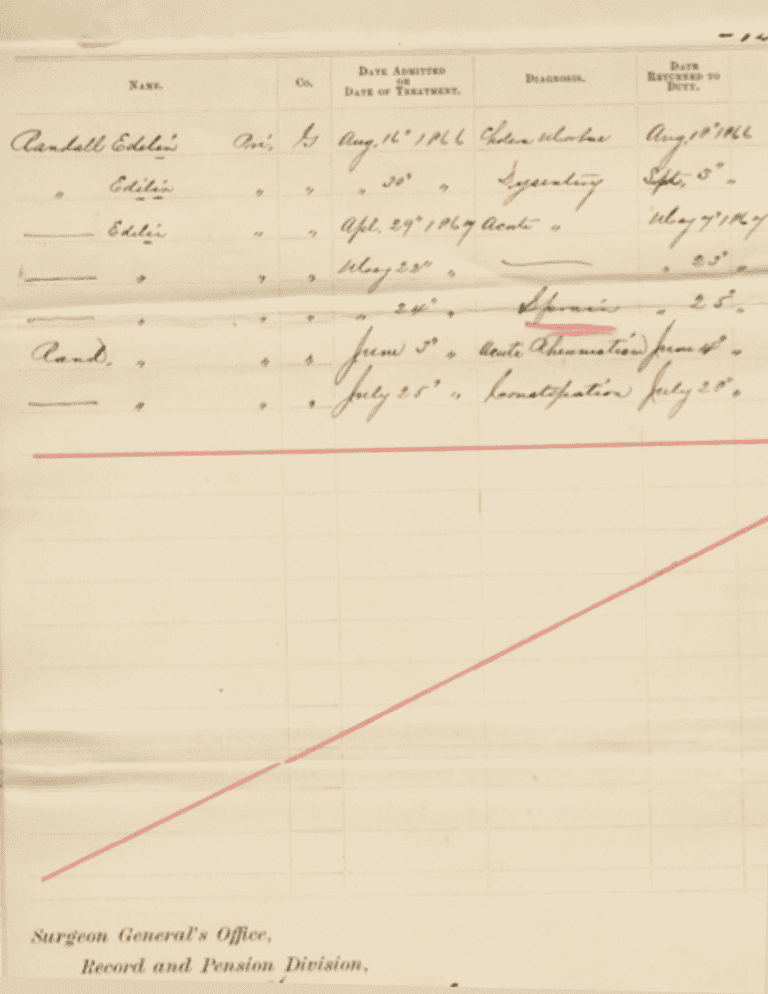

Though stricken with sickness and injury numerous times during his service, he completed his full tour of duty. He served as a private in Company G of the 125th Colored Infantry and after several illnesses, including cholera and acute dysentery, was assigned daily duty as a cook until being mustered out on October 31, 1867.

He and Mary had an additional child, Addie, in 1870, and when not too infirmed, he worked as a blacksmith and was listed in the 1870 and 1880 Census as such.

According to his very extensive pension files, he suffered from significant health complications during the last years of his life that included a back injury suffered attempting to move a box of blacksmith tools that may have fallen into a swollen Rio Grande River while serving in the USCT in Fort Bliss, Texas. His files indicate that he was also diagnosed with piles, prolapsus ani, cystitis, lymphoma, cholera, dysentery, acute rheumatism, and eventually died on April 29, 1888, from Uremic Poisoning, which is a consequence of kidney failure.

Author’s Note

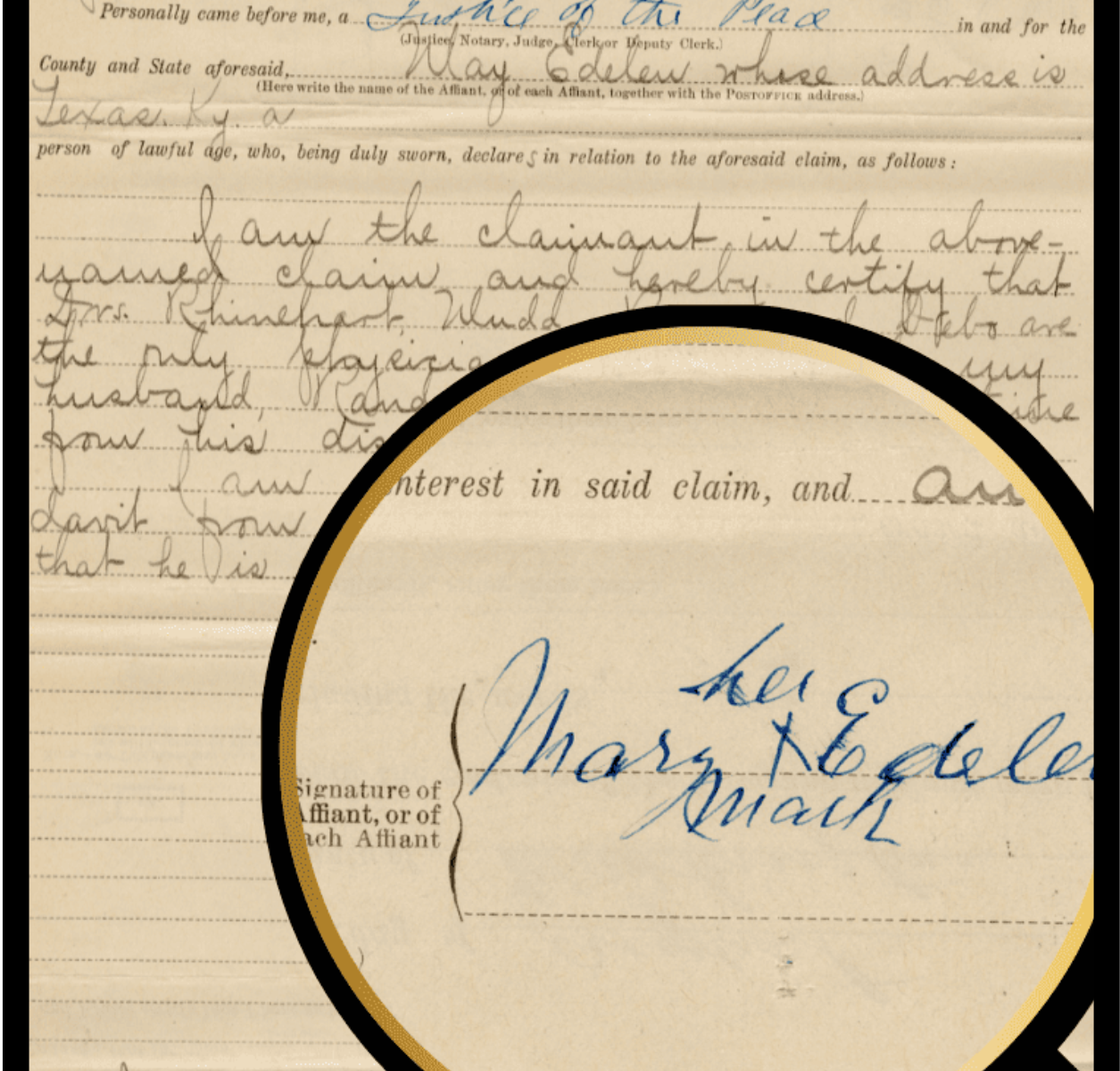

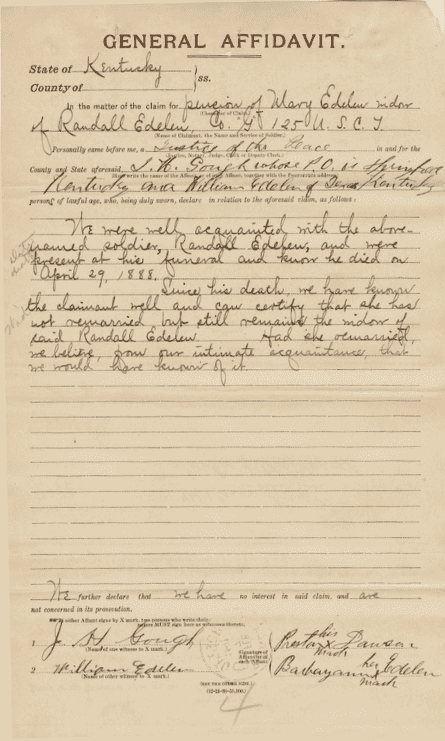

The Edelen family’s challenges that were documented in 90 pages of pension files, military service records, census records, and Freedman’s bank notes, were simultaneously uplifting and heartbreaking to read. The most moving part was getting to see Mary Edelen, my 3rd Great-great grandmother’s mark on multiple documents and most powerfully on the affidavit where two of her own children serve as witnesses. Seeing the X in place of her signature made the X, from a legal name change in my own name, even more significant. It was as if my ancestors had been speaking to me from across time.

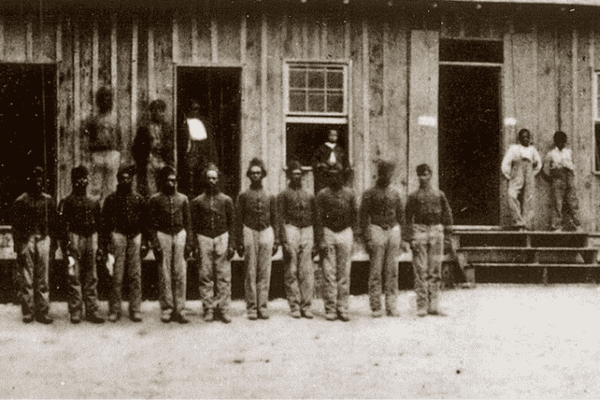

The poems “Check Out Time,” “Affi-davits,” and “Mother May I” are persona poems in the voices of Mary and Randall Edelen, and they were inspired by these documents. Discovering that Randall Edelen “enlisted without consent” was a reminder of the degree to which enslaved peoples resisted bondage and a point of pride to imagine all the subtle and outright ways my ancestors insisted on their own freedom. The poems “Grove” and “Coming of Jubilee” are ekphrastic poems inspired by the Camp Nelson photo that appears as the cover photo on the Kentucky U.S. Colored Troops Project web page.

Frank X Walker

Affidavits

Mary X Edelen, Civil War widow

Them make me scratch out a X

in ink with two witnesses

on afta-Davids

to prove me and Randal was married.

I fetched afta-Davids

from every doctor still living

that examined

my husband’s piles

and old man’s bladder,

witnessed his pain,

and still doubted his suffering

while he rot from the inside.

Them even bade me make my mark

afta-David

with more witnesses

to prove my Randal was dead and gone.

They made me X the page

with witnesses so many times

on so many pension papers

that though I can not read

or write a lick,

I come to recognize

my own name when I see it.

The fancy M on Mary come to look like

a woman keep changing her mind.

And the E them like to put on Edelen,

a tired old bitty in a bonnet

who done set herself down an quit.

I first think my mark look like

a tired ol’ cross,

but after a while I come to see

a long sharp knife

like my Randal’s old scabbard from de war.

Affidavits

By Frank X Walker

From his book Load in Nine Times

Frazier History Museum

Louisville, Kentucky

October 8, 2024

If you choose to purchase Load in Nine Times at amazon.com through the link provided, Reckoning will earn a small commission.

Grove

Photo of Troops outside

the Colored Soldiers Barracks,

Camp Nelson

This was the first time

we really look at each other

and not be able to tell

who master the cruelest

who sorrow the deepest

who ground been the hardest to hoe.

We was lined up like oaks in the yard

standing with our chins up,

proud chests out, shoulders back,

and already nervous stomachs in.

We was a grove wanting to be a forest,

ready to see what kind of wood we made from.

The only thing taller or straighter

than us be the boards

holding up the barracks at our backs,

though most our feets feel pigeon-toed

and powerful sore

from marching back and forth, every day,

for what seem like more miles

than we walked to get here.

It take more than pride to stand still

’neath these lil’ hats not made for shade.

Soldiering ain’t easy, but it sure beats

the bloody leaves off a bondage.

Checkout Time

Randall X Edelen, Company G,

125th U.S. Colored Infantry

It was good money

if you lived to collect it.

I was luckier than most.

It took a strained back

to slow me down enough

to catch one a them fevers

that travel through camps

with bad water

and not enough clean places to shit.

More of us catched the runs

an died from disease

in hospital beds than from bullets.

When I had the cholera

they mark me present, but sick.

When I catched the bloody flux

they mark me present, but sick.

Somehow, I survived, though it costs

Me my livelihood.

It costs many more men their lives.

This is what them mean

when they say freedom ain’t free.

Mother May I?

Randall X Edelen, Company G,

125th U.S. Colored Infantry

Took almost four years

and a whole lot a dead, white bodies

to figure out they needed Kentucky

to win the war.

In March of ’65 the gov’ment

said joining the Union Army

guaranteed freedom for each new soldier

and our families too.

Come April, I found my way to Lebanon

an signed my mark in ink for my Mary

and our John, Susan, William, Sallie,

Daniel, Scott, and Silas.

I’m sure Miss Jane felt like

she been robbed

losing nine slaves all at once

with the power of my X.

I know she had some unkind words

for good ol’ Lincoln and the Gov’nor

who only offered her $300

for what them called compensated

’mancipation.

Knew she’d be fit to be tied so,

I didn’t ask.

I enlisted without consent.

It might look like we standing

on solid ground,

but we got all our feets on faith,

not in a country or a president,

but in the belief

that waiting on the other side

of whatever the Lord see fit

to put in front a us

be a chance to be free.

We ain’t running away

to find freedom for our families,

but marching toward it

—with guns in our hands.

Penmanship

Mary X Edelen, Civil War widow

i woulda knowed

who longhand was who

even if I didn’t see ’em

scratch out they names

on the paper

to swear my X is mine.

my William be proud,

like his daddy

he address his letters as pretty

as he dress his self.

his ink ease off the quill

just as smooth

as words off his tongue,

but my Scott and his letters

seem to take the long way

’round, make big slow loops,

and care not if they spine

stand up straight or not.

my Will glides ’cross them lines

like they pretty hardwood floors

while my Scott,

more accustom to dirt,

seem half ’fraid to touch ’em.

Frank X Walker

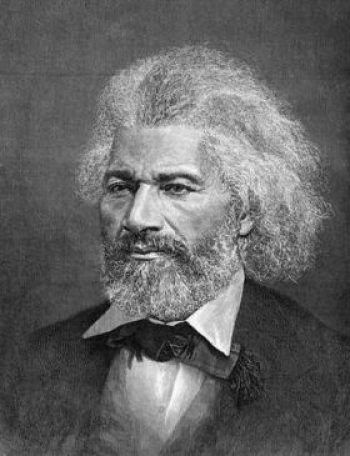

Danville, Kentucky native, multidisciplinary artist and educator, Frank X Walker, is the first African American writer to be named Kentucky Poet Laureate. He is the author of the children’s book, A is for Affrilachia, and thirteen collections of poetry, including Turn Me Loose: The Unghosting of Medgar Evers, which was awarded the NAACP Image Award for Poetry and the Black Caucus American Library Association Honor Award, Buffalo Dance: The Journey of York, which won the Lillian Smith Book Award, Isaac Murphy: I Dedicate This Ride, which he adapted for stage, earning him the Paul Green Foundation Playwrights Fellowship Award, and his latest, Load In Nine Times.

Voted one of the most creative professors in the south, Walker coined the term “Affrilachia” and co-founded the Affrilachian Poets. His honors include a Lannan Literary Fellowship for Poetry, two Denny C. Plattner Awards for Outstanding Poetry, West Virginia Humanities Council’s Appalachian Heritage Award, as well as fellowships and residencies with Cave Canem, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Kentucky Arts Council. In 2020 Walker received the Donald Justice Award for Poetry from the Fellowship of Southern Writers. He is the recipient of honorary doctorates from the University of Kentucky, Transylvania University, Spalding University, and Centre College. He serves as Professor of Creative Writing and African American and Africana Studies at the University of Kentucky.

More information can be found at FrankXWalker.com