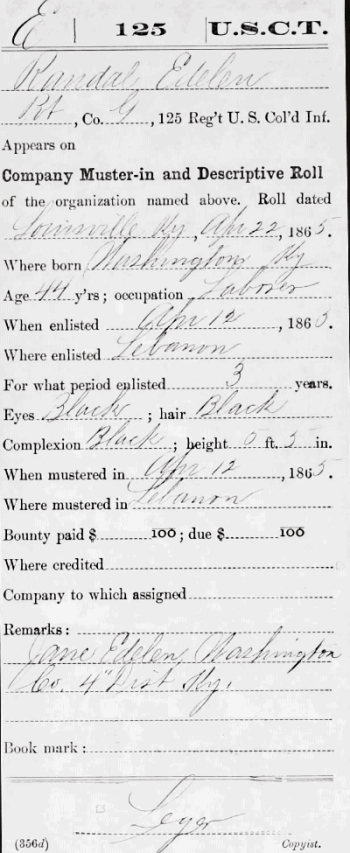

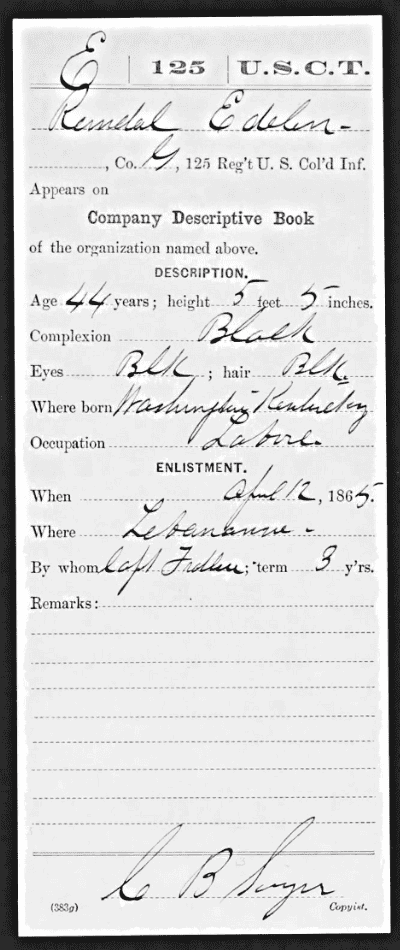

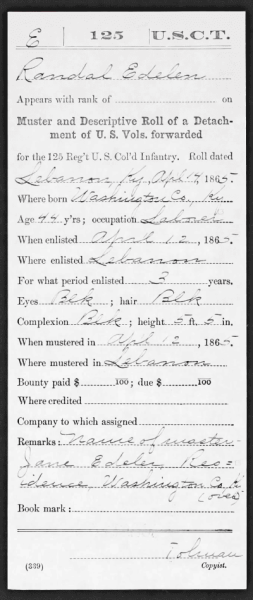

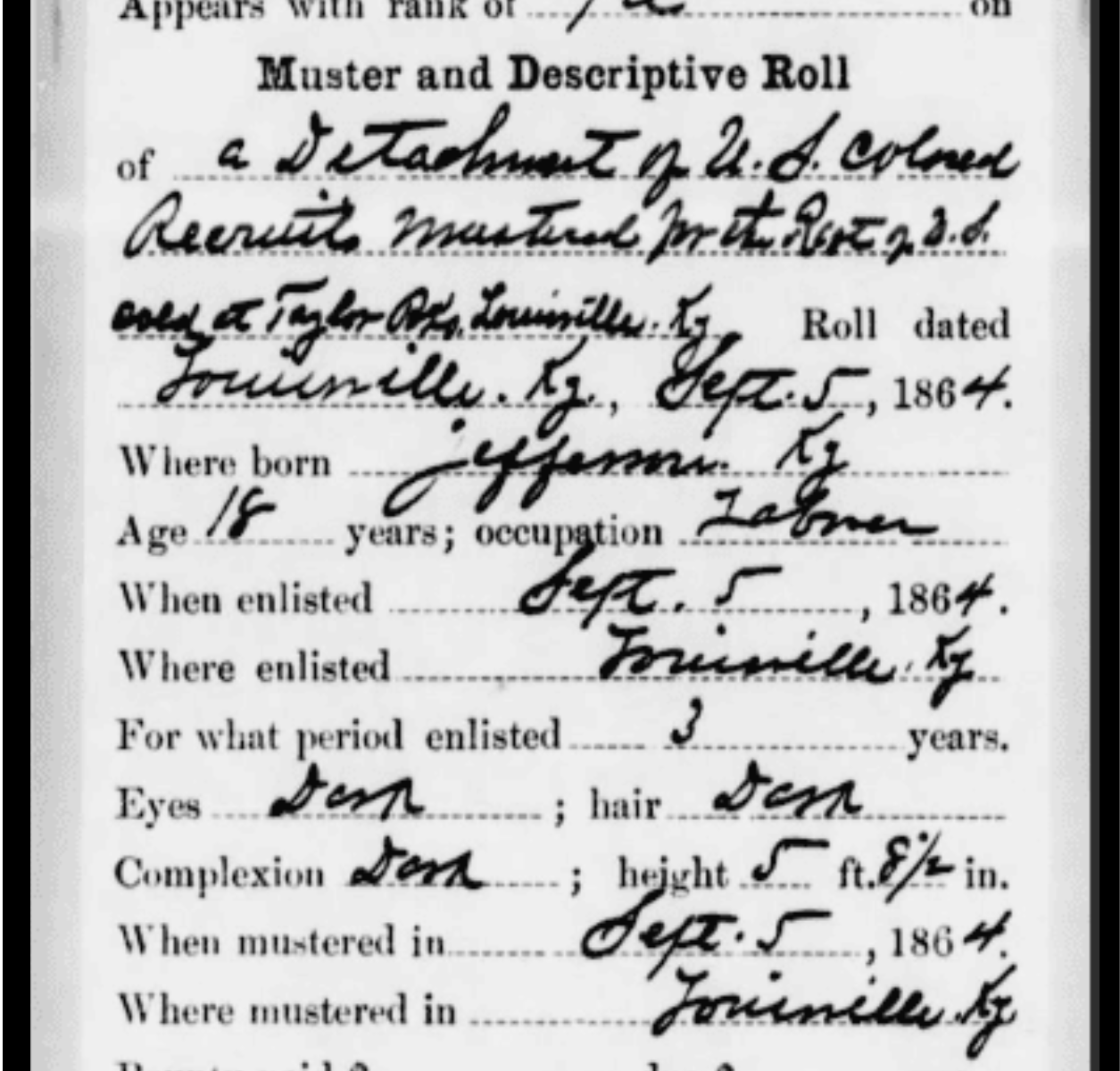

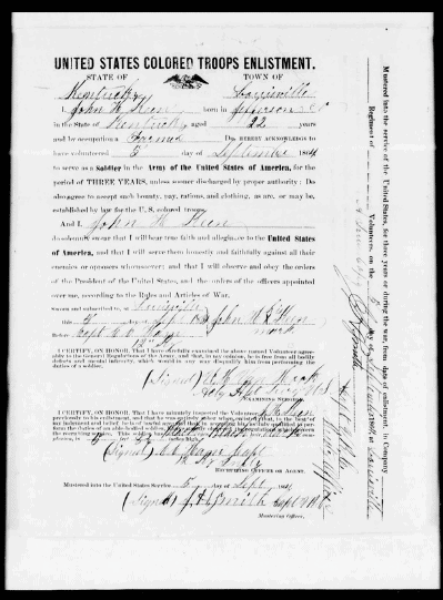

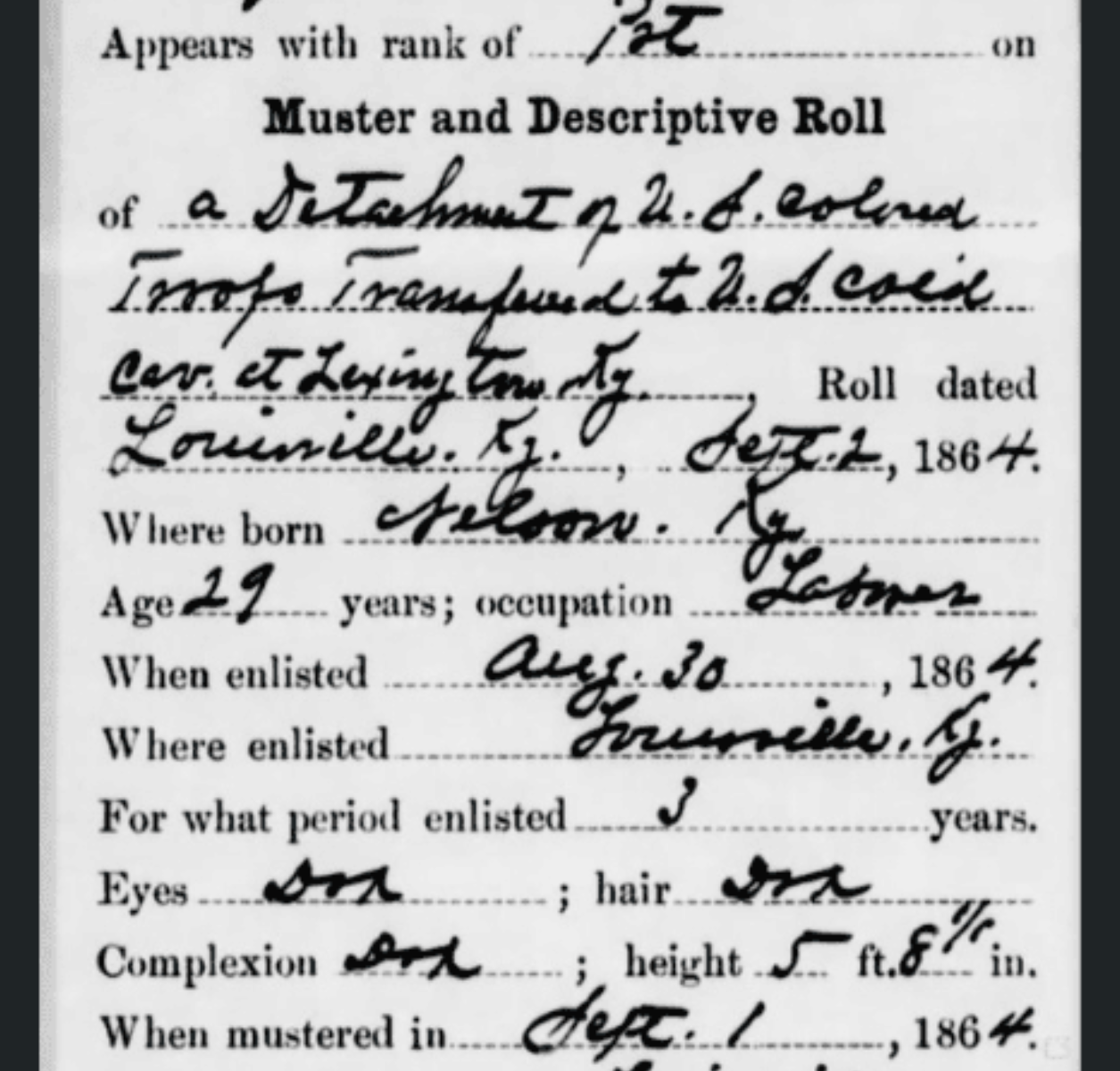

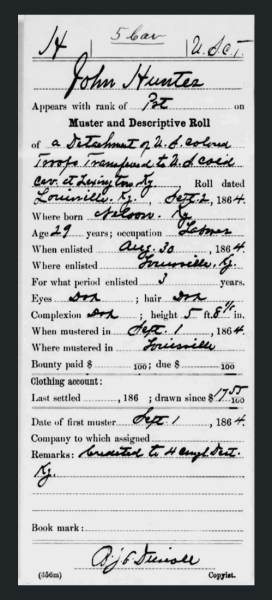

1 “U.S., Descriptive Lists of Colored Volunteer Army Soldiers, 1864” database, Ancestry.com,

https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2132/images/32733_520307095_0290-00150

2 ibid

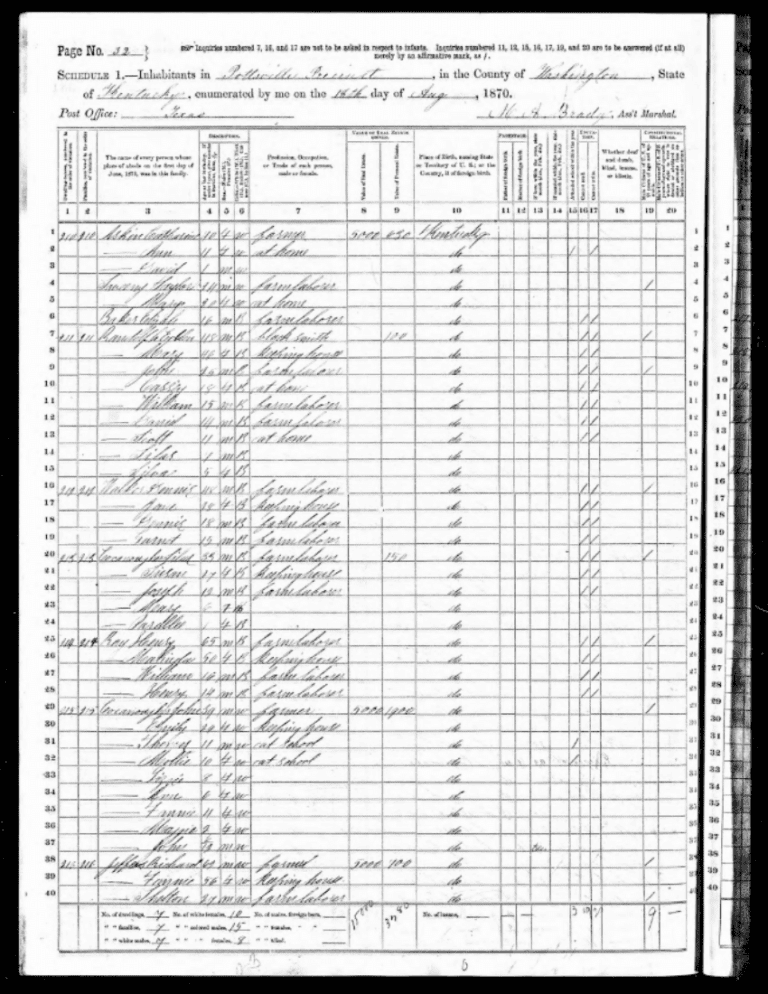

3 U.S. Census Bureau, “1860 Federal Census” Ancestry.com,

https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/7667/images/4231200_00193

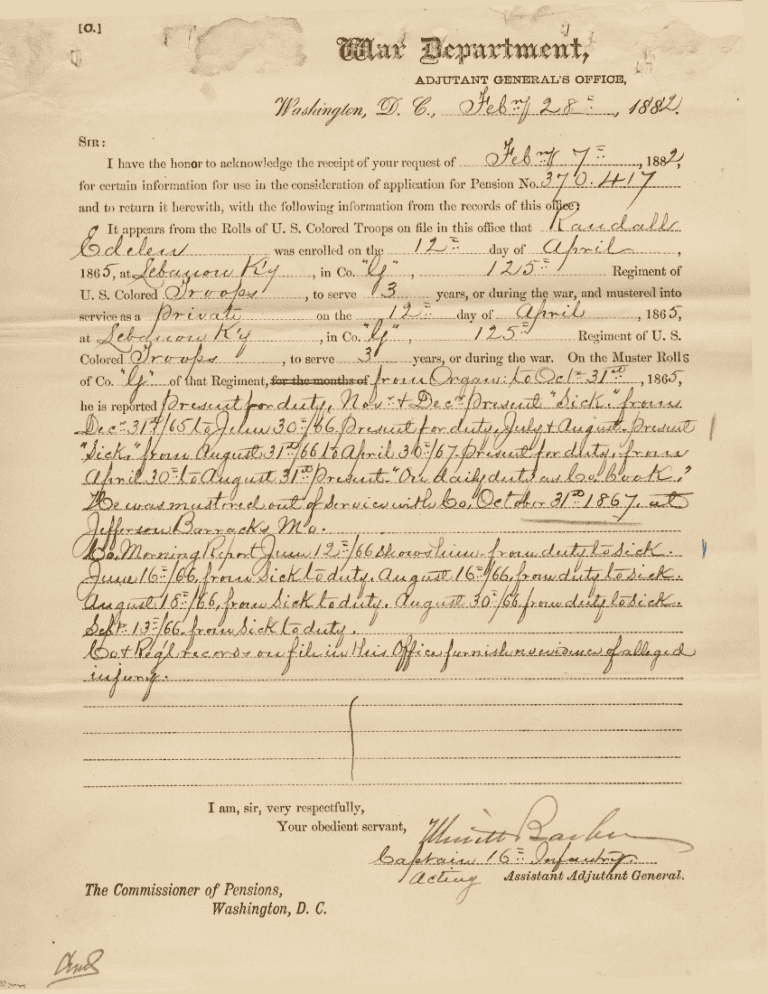

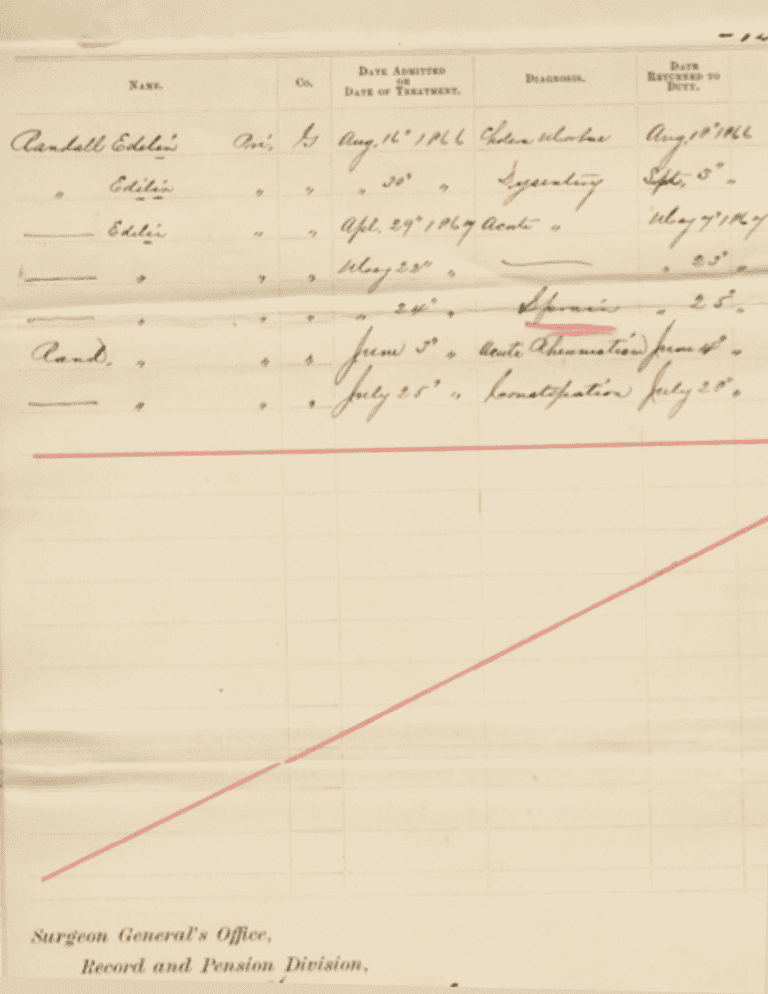

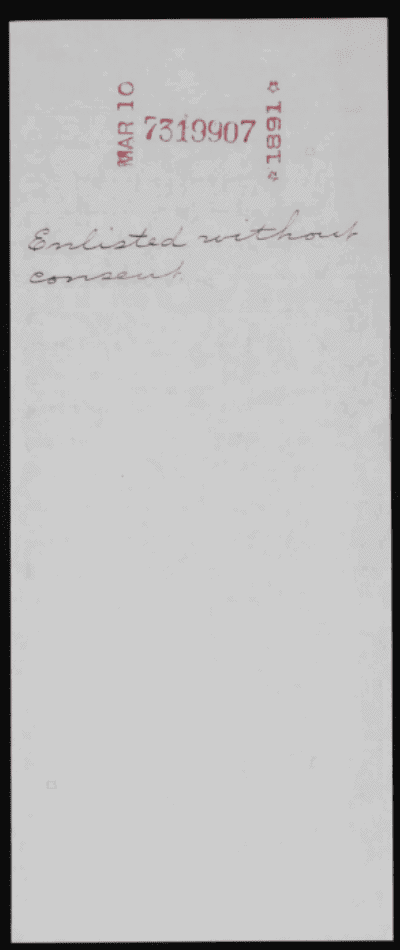

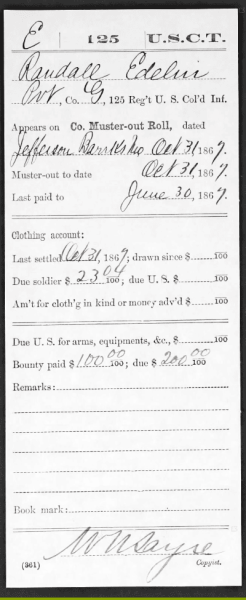

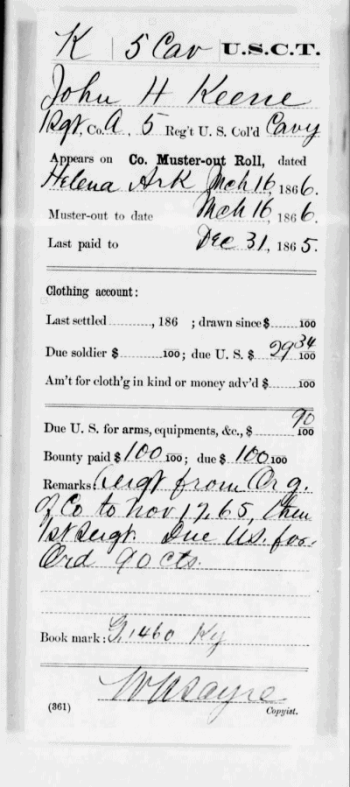

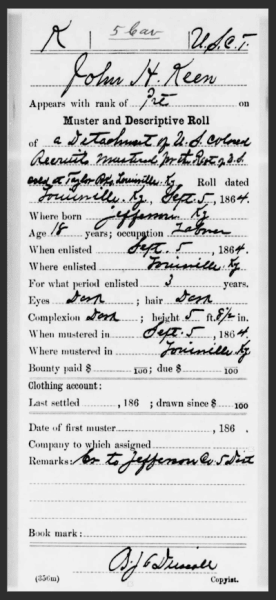

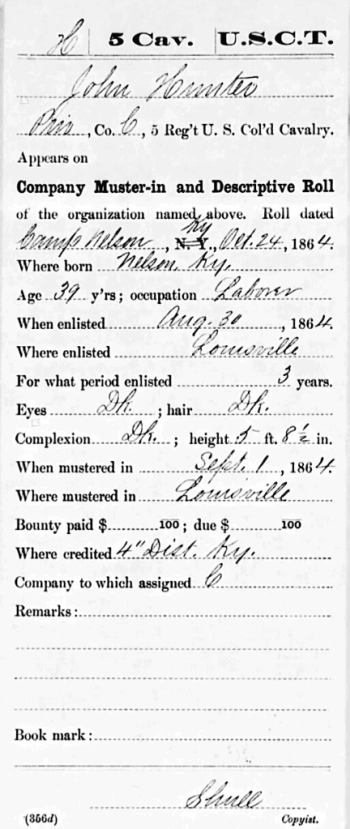

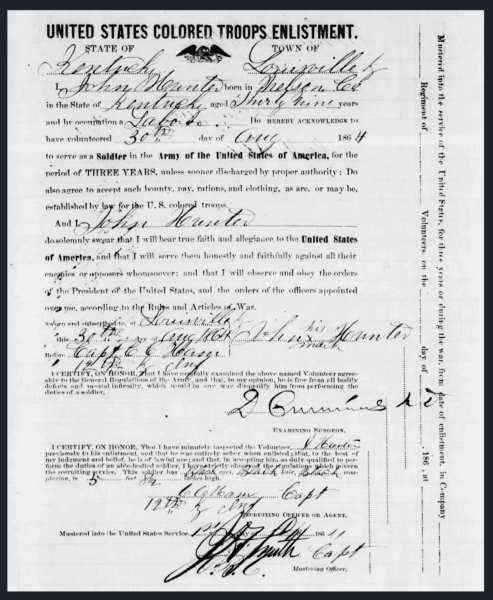

4 Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served the United States, Colored Troops: 56th-138th Infantry, 1864-1866,

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1MFVWAiPMbfRpSeOD6yO53eiruC44pyWk/view

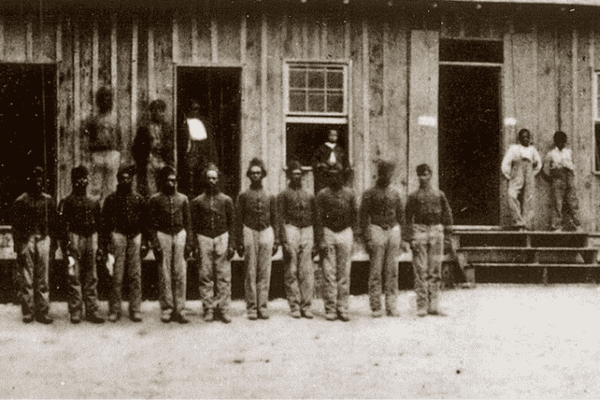

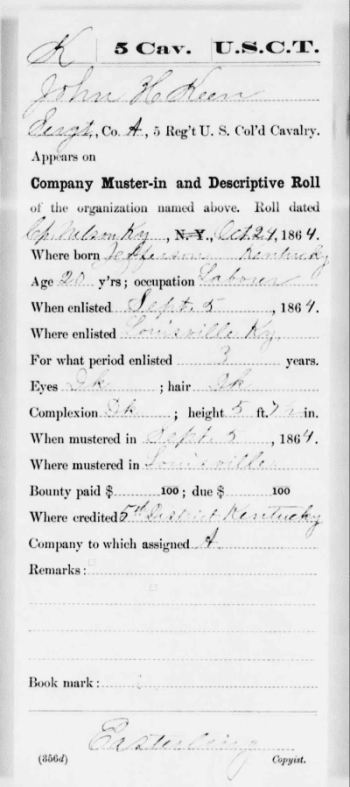

5 National Park Service, “United States Colored Troops 5th Regiment United States Colored Calvary,”

https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-battle-units-detail.htm?battleUnitCode=UUS0005RC00C

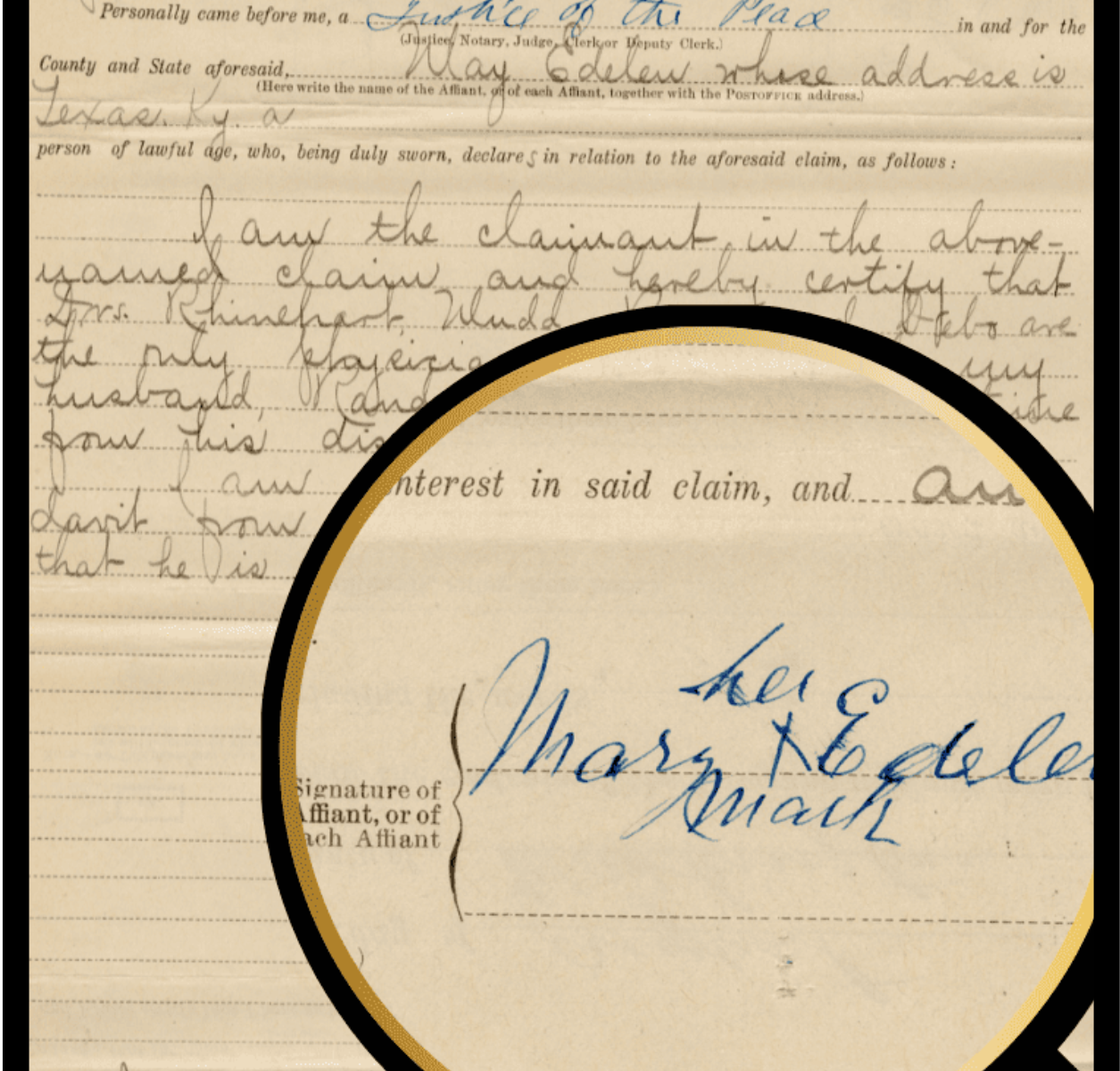

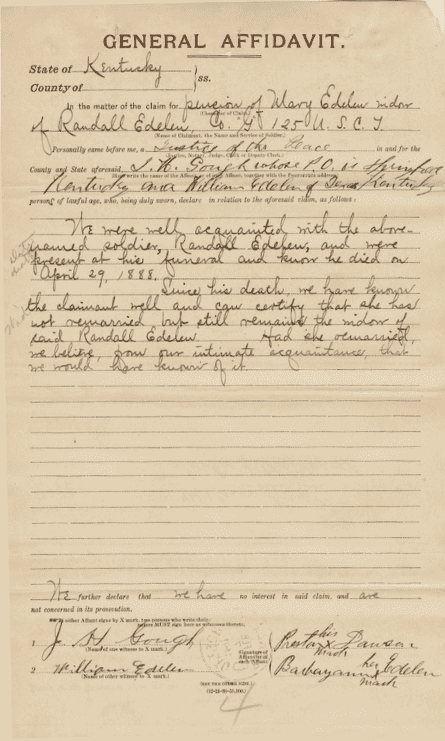

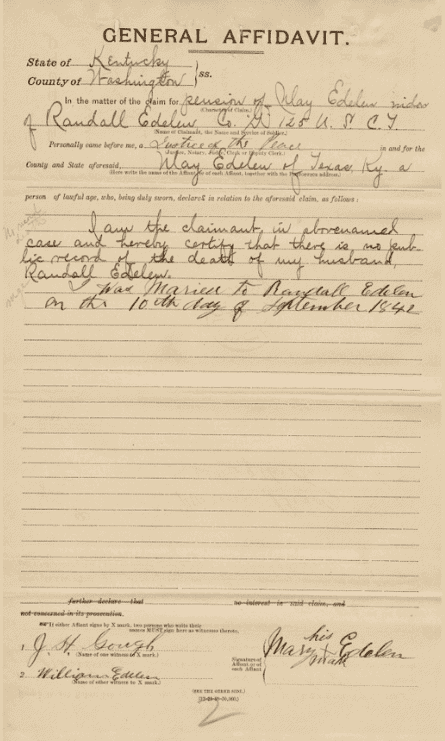

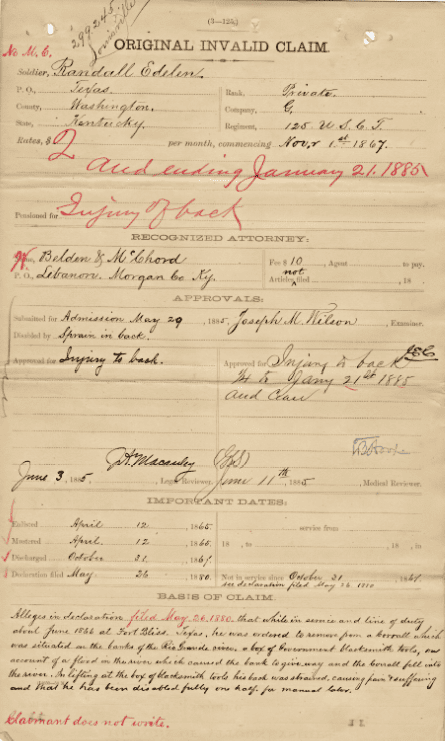

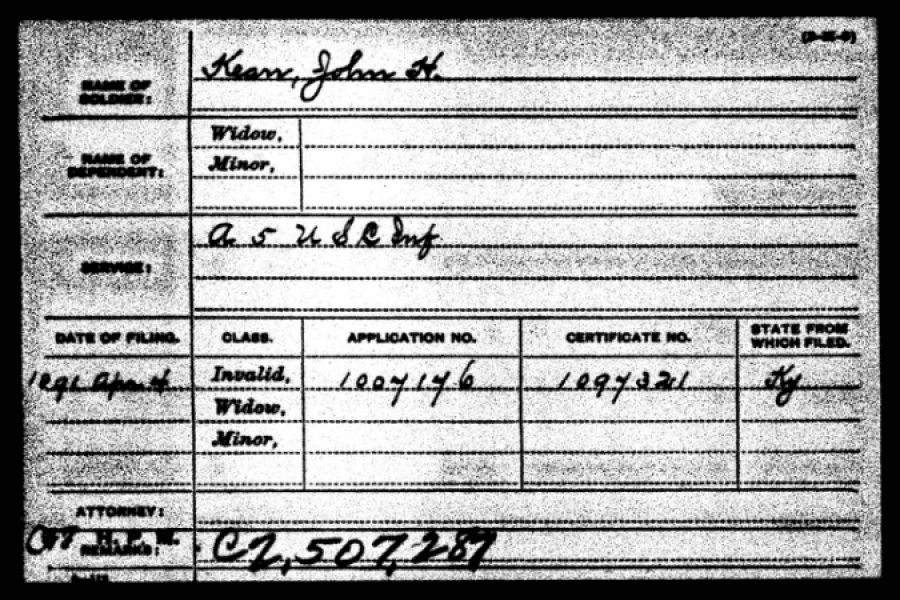

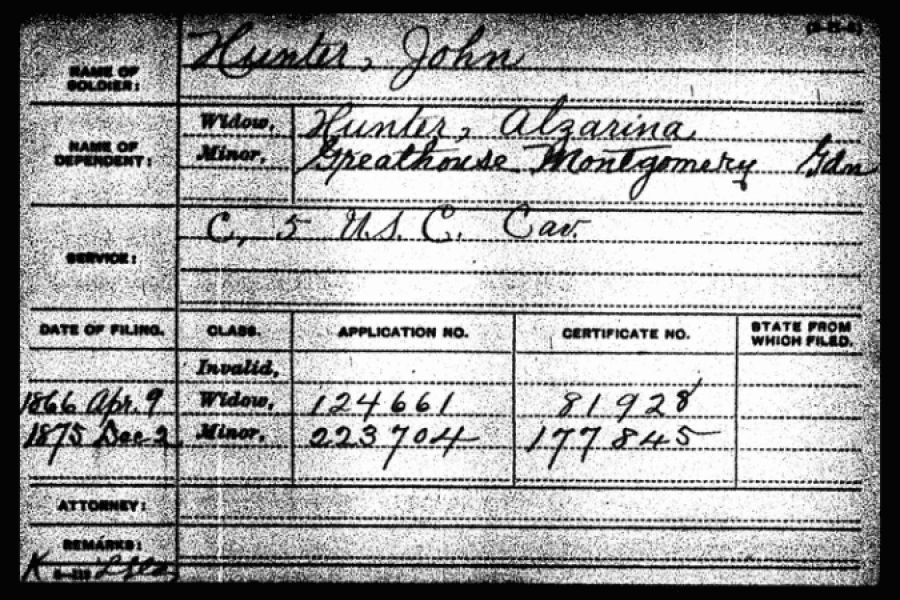

6 Civil War, Widow Pension Files, “Widow’s Application for Army Pension”,

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1P5Ln11ubEKbL4hqrPJte4WTgf6AVvuDB/view?usp=sharing

7 U.S. Freedman’s Bank Records, 1865‐1874, Ancestry.com,

https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8755/images/KYM816_11-0311?pId=215289

8 U.S. Freedman’s Bank Records, 1865‐1874, Ancestry.com,

https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8755/images/KYM816_11-0432?pId=82716364

9 Civil War, Widow Pension Files, “Widow’s Application for Army Pension”,

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1P5Ln11ubEKbL4hqrPJte4WTgf6AVvuDB/view?usp=sharing

10 ibid

11 ibid

12 National Park Service, “Saltville Battle and Massacre,”

https://www.nps.gov/cane/battle-of-saltville-and-massacre.htm

13 ibid

14 ibid

15 ibid

16 ibid

17 ibid

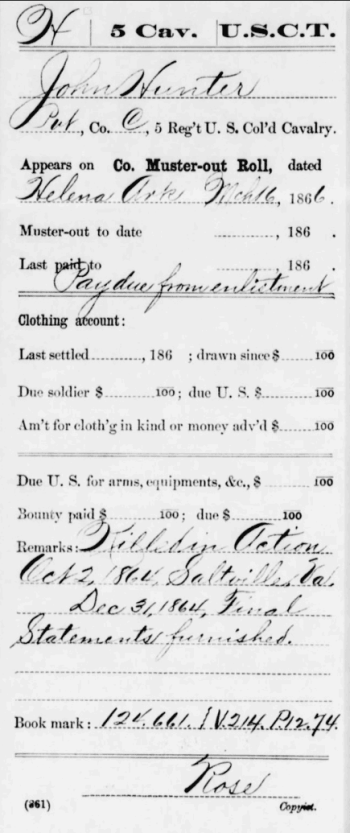

18 Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served the United States, Colored Troops: 56th-138th Infantry, 1864-1866,

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1MFVWAiPMbfRpSeOD6yO53eiruC44pyWk/view

19Civil War, Widow Pension Files, “Widow’s Application for Army Pension”,

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1P5Ln11ubEKbL4hqrPJte4WTgf6AVvuDB/view?usp=sharing

20 U.S. Freedman’s Bank Records, 1865‐1874, Ancestry.com,

https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8755/images/KYM816_11-0432?pId=82716364

21 Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served the United States, Colored Troops: 56th-138th Infantry, 1864-1866, Montgomery Greathouse,

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1HLfTkVyvzqOOcWdNNGqYq6YMj0ysRvwd/view

22 Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served the United States, Colored Troops: 56th-138th Infantry, 1864-1866, Moses Greathouse,

https://drive.google.com/file/d/18Wl6Qr4AK_s0T9NPUQRYlvuSHKnfZIgr/view

23 Civil War, Widow Pension File, “Proof of Cohabitation-Joint Affidavit,”

https://drive.google.com/file/d/14pkMRFFmBxD9DPOvQmDJb0r2UBuf5gT9/view?usp=sharing

24 Civil War, Widow Pension Files, “Claim for Widow’s Pensions,” https://drive.google.com/file/d/1gXQi2iQezad0dt32S7dQSz0MslOsaRx2/view?usp=sharing

25 Civil War, Widow Pension Files, “Widows Application for Increase of Pension,”

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1bPm0_7r2nER6SUXf0MWL9-Y2jh9gmVGK/view?usp=sharing

26 Civil War, Widow Pension Files, “Evidence of Minor Children’s Date and Places of Birth,”

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1SBb7UBrNaWgt36hLFwDf1dq0Ow9IiAf9/view?usp=sharing

27 Civil War, Widow Pension Files, “Increase of Pension Additional Evidence: Joint Affidavit,”

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1JClPyPtUO45Uxd1iNCE3G4nFKP7gFgQf/view?usp=sharing

28 Civil War “Widow’s Pension File”, Ancestry.com,

https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/tree/182661613/person/232378978129/media/557bb5ac-0bc3-4603-b42e-7caf04718327

29 U.S., Death Records 1852-1965, Ancestry.com,

https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1222/images/kyvr_7007126-0611?pId=22715

30 Civil War, Heir Pension Files, “Letter of Guardianship,”

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1NxZFYz26PFZonfG6B2-KSshw2eFVBbd5/view?usp=sharing

31 Civil War, Heir Pension Files, “Claim of Guardian of Orphan Children for Pension,”

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1QyvhxBGg-q56Akm_R1k6lvaIKtLtB26w/view?usp=sharing & https://drive.google.com/file/d/1TGGCHLOETpPoE6CepXtQ5vi0dSnS5unv/view?usp=sharing

32 Civil War, Heir Pension Files, “Case of Hunters Heir”, “Exhibit A,”

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1S2lbko7sih7TXIZwYdbLMcGaxXCcKZ6z/view?usp=sharing

33 Civil War, Heir Pension Files, “Case of Hunters Heir”, “Exhibit B,”

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1GO6VFb7bhL5uoTRc2Ly8kj5NuWhXVJKo/view?usp=sharing

34 Civil War, Heir Pension Files, “Case of Hunters Heir”, “Exhibit E,”

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1XK-A7JuRV4dQuTUdIyaRXOlsPsWaYimB/view?usp=sharing

35 Civil War, Heir Pension Files, “Case of Hunters Heir”, “Exhibit F,”

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1W4HL-hXFFHrtIVxgNP3iQAxBTRVmgDlA/view?usp=sharing

36 Civil War, Heir Pension Files, “Case of Hunters Heir”, “Exhibit I,”

37 Civil War “Widow’s Pension File”,

https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/tree/182661613/person/232378978129/media/557bb5ac-0bc3-4603-b42e-7caf04718327